When Brett Wille began as the principal at Hidden River Middle School in Monroe five years ago, he and his staff set out to create a culture shift. He saw an opportunity to improve the way the school met students’ needs, as well as strengthen relationships and collaboration between teachers. Since then, in close partnership with his staff, they have created “a school that we’d bring our kids to.”

“The focus on culture is the foundation of everything” Wille said. “We have a vision for what we want to be,” and for their shared purpose: essential skills for every student.

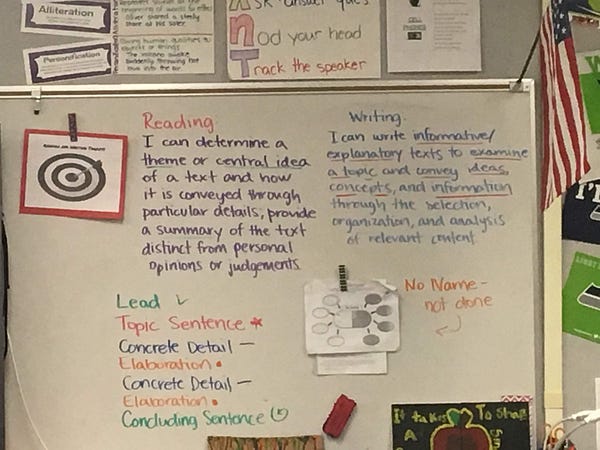

What does the culture shift look like in classrooms? Teachers talk less, while students talk more. “Quiet is not productivity,” Wille said.

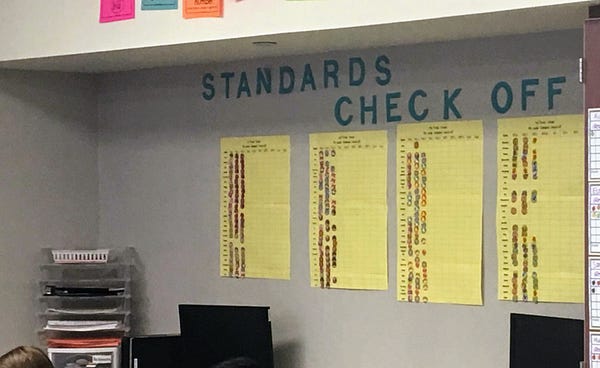

Learning standards form the foundation of instruction, and teachers use data to drive continuous improvement cycles as part of their professional learning communities (PLCs). “We actioned the standards to drive the work,” said assistant principal Jonathan Judy.

Learning standards form the foundation of instruction, and teachers use data to drive continuous improvement cycles as part of their professional learning communities (PLCs). “We actioned the standards to drive the work,” said assistant principal Jonathan Judy.Students take ownership of their learning and set weekly goals addressing academics and behavior, as well as planning for high school classes.

Discipline issues have decreased as staff promote positive choices with students and take a proactive, rather than reactive, approach.

Students in special education are integrated into general education classrooms as much as possible using a co-teaching model.

“We have teachers who are trying to meet every kid where they are,” Wille said.

Grade-level classes for every student

One reason that Wille committed to a culture overhaul was the way the school was educating students with disabilities who have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). “We were pulling them out of grade level classes,” he said.

The school has implemented a co-teaching inclusion model that provides every student with access to instruction of grade-level standards.

“The farther from general education that students get, the less likely they are to get a standard diploma and access to a job,” said Nicholas French, Director of Curriculum and Assessment for the Monroe School District. “Access to the classroom is access to independent life.”

In Tara Bennett’s 8th grade English and history classroom — as in other inclusive classrooms at Hidden River — the two teachers aim to address the learning needs of each student. Students with IEPs are indistinguishable.

“Inclusive classrooms are not a shiny ball,” Wille said. “They look like engaged classrooms.” While one teacher leads instruction, the other moves quietly around the classroom supporting students as needed.

Bennett is in her third year with the co-teaching model. She said it was scary at first, but now: “it is a breath of fresh air.” She is the content specialist, while her co-teacher “looks through the eyes of the learner.” But they both teach and support students individually.

“I grow as a teacher. I’m learning new ways to support students in success,” Bennett said.

Successfully shifting to an inclusion model required many types of ongoing support from Wille, such as time for teachers to engage in professional development and PLCs. “We are a team working for kids,” Bennett said.

Students with IEPs who need more support also take a life skills class where they can work on their individual goals, which could range from social interactions to appropriate behavior.

“The model here enables us to try different things to meet students needs, and find the appropriate placement during the course of middle school,” said life skills teacher Ashley Castillo. “We try a lot of things and adjust as needed.”

‘Actioning’ learning standards

On a recent fall morning, Wille greeted students in between classes. On the walls of the hallway are inspirational quotes, along with bulletin boards featuring learning standards and samples of student work aligned to those standards. “Making the work visible” is part of how staff stay accountable to each other and maintain transparency about their work, Wille said.

On a recent fall morning, Wille greeted students in between classes. On the walls of the hallway are inspirational quotes, along with bulletin boards featuring learning standards and samples of student work aligned to those standards. “Making the work visible” is part of how staff stay accountable to each other and maintain transparency about their work, Wille said.In a 6th grade English classroom, students worked on writing leads. Wille walked around the room talking with students, as he often does. When he visits classrooms, he poses three questions to students: what are you learning? How do you know you’ve learned it? What are the next steps?

School staff have set a goal to “close the gap,” so that in the current school year, every student meets grade level proficiency or improves by one level on the Smarter Balanced assessment (SBA). The school already performs better than state averages on the SBA, with nearly 70 percent of 8th graders meeting standard in English, and almost 65 percent scoring proficient in math.

The learning standards are “vertical,” Bennett said, supporting learning that builds from year to year. The school has grade-level teams that break down learning standards and regularly discuss what proficiency looks like. Wille provides professional development time for this work.

Bennett said teachers collaborate with each other to calibrate grading so that students’ work is judged consistently no matter their teacher.

“We rely on our colleagues to support student success,” she said.

Teachers also talk through the standards with students and use them to support students in developing academic goals.

Future focus and goal setting prepare students for high school transition

Connecting classroom work to future plans is also important at Hidden River. The school is committed to ensuring that every 8th grade student completes a High School and Beyond Plan. Health teacher Katy White has led the effort.

“Relevancy has to be there,” White said.

She has developed lessons to deliver in the fall of the 8th grade during health classes, which is an appropriate venue because those classes are already focused on goal setting.

White created a step-by-step checklist to keep students organized as they work on their Plans and to prevent overwhelm from too much material as they prepare for high school course registration. She prints out the high school course catalog for students to review and keeps in touch with counselors at the high school to stay up-to-date and check in on students.

Students often ask her why they must consider all four years of high school when they are picking 9th grade classes. “We need to look at the big picture to make sure that four years of courses add up to graduation,” White said.

Having life all mapped out is not the point, White said. She tells students, “You don’t have to have it all figured out, but you should set goals.”