In fall 2018, Che Teeters enrolled in the Open Doors program at Lake Washington Institute of Technology (LWTech) after talking to an advisor at LWTech. Teeters had not graduated high school, a step that was holding him back on his career pathway. He decided to enroll in Open Doors to graduate high school and have more career opportunities.

“I wanted a better life,” Teeters said. “I wanted to give myself a second chance.”

At first, Teeters was concerned when attending classes through Open Doors because of his past negative experiences in school. However, he discovered that classes could be fun and interesting.

“Professors treated me like an adult, I was allowed to question things, I didn’t feel moronic for asking a question or needing a bit of extra time,” Teeters said. “It felt like I finally had found that I could learn and there were downs with the ups, but it never lasted too long.”

Justin M. had similarly discouraging high school experiences. After experiencing symptoms of serious mental illness, Justin was hospitalized for up to six months in middle school and high school. Through this time, he recovered and learned to manage his mental health challenges. However, due to his absences, Justin’s high school labeled him “truant” and sent him to an alternative school.

“I felt like I’d overcome a huge hurdle but had no idea how I was going to graduate, and the system didn’t care,” Justin said.

Justin decided to enroll in Open Doors at LWTech. While taking transition courses and then college courses, he felt cared about and challenged.

“I learned to find my worth internally,” Justin said. “Open Doors and being in the college environment showed me that I was smart, after having been told I was stupid or behind for so long. I began to feel hope about the future again and felt excited about education for the first time ever. The sheer possibilities of extending the frontiers of knowledge made my stomach flutter, and this was something I had never experienced before.”

Students in our state have education and career aspirations, but they may have faced barriers – such as housing or food insecurity, addiction, or chronic illness – that prevented them from graduating high school. According to the Road Map Project, a collective impact organization working to increase equitable policies and practices so that 70 percent of South Seattle and South King County students earn a college degree or career credential by 2030, students disengage from high school for a number of interwoven reasons: “Disengagement is a complex experience that is often the result of multiple interrelated school and individual factors together that, over time, push students out of school.”

In Washington state, nearly a tenth of students, about 120,000, were pushed out of school because of these complex circumstances, which affect some students of color disproportionately – including American Indian/Alaskan Native, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander – as well as students learning English, students in foster care, students who are homeless, students with disabilities, and students from low-income backgrounds.

Open Doors is a reengagement effort that provides individualized education and services to young people ages 16-21 who have dropped out of school or are not on track to graduate from high school by age 21, enabling a new opportunity for young people to earn a credential after high school – such as a degree, apprenticeship, or certificate – in a field of study and with supports that fit their needs and hopes. Increasingly required for many jobs in Washington state, a credential also helps protect people from changes in the economy.

Earning college credit while working toward a diploma

Students who participate in Open Doors often take classes on community college campuses, which can be an encouraging experience.

“Students feel like they’re moving forward, instead of feeling like they’re held back,” say Devin Blanchard and Lillian Martz, two licensed school counselors who have worked with Open Doors students. “Instructors do not know that you are an Open Doors student, they just think of you as a student. Students can feel pride about being back in school as opposed to shame.”

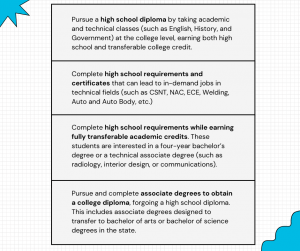

Many community colleges across Washington have Open Doors programs that grant dual credit, which means students can receive high school and college credit at the same time. With Open Doors, students can work toward a variety of outcomes, from pursuing a high school diploma to earning college credit toward a post-high school credential and more (see below).

Learning valuable academic and life skills

As part of many Open Doors programs, students explore careers, such as the variety of options in the education and healthcare fields beyond teaching and nursing. They complete assessments to think about how to apply their strengths, values, and interests to their education and career goals. Students may also take a College Success class that involves building skills like note-taking and time management.

Many Open Doors programs also have courses designed to teach life skills – including how to budget, open a bank account, invest, and file taxes – as well as to promote success in education after high school, such as financial aid, applying to college, writing resumes and cover letters, and building interviewing and communications skills.

Setting goals using the High School and Beyond Plan

As students explore and learn, they use the High School and Beyond Plan (a Washington state graduation requirement) to map out their individualized pathway with relevant projects. For example, a student who is planning to enter the military after receiving their diploma might choose to meet with a recruiter or interview an active duty servicemember. If a student plans to complete an associate degree in welding, they might shadow a welder. A student interested in becoming a forensic criminologist could interview someone in the field and research how to apply to the University of Washington.

“High School and Beyond Planning is valuable because it is individualized for students’ goals and it can be flexible over time,” Blanchard and Martz said. “We do it in pencil so we can go back and erase, not committing to a path 100%. If students realize that a career they wanted is not a good fit, they can make that change and explore other options.”

Students learn about both academic and personal goal setting and even when their goals change, they can set new objectives and a plan for achieving them.

At LWTech, Teeters – who has always been fascinated by technology – experienced changing his goals. At first, he planned to study computer science and software development. However, after a few classes, he felt unmotivated and bored. He decided to shift gears and take classes in computer security and network technology.

“I had so much fun almost immediately, I found people who had similar interests to me and even a few who had the same issue with programming that I did, and the things learned felt new and exciting every day,” Teeters said. “I learned so many things that I never even knew existed and honestly, there’s so much more involved than a lot of people think when it comes to IT.”

Students progress toward their goals while receiving support

Through exploring careers and college programs, as well as interviewing and shadowing professionals, many students have discovered career paths they are passionate about, such as auto repair, public health, and medical assisting. Advisors support students at each step to think about ways to achieve their goals.

According to Blanchard and Martz, academic and behavioral standards are key to the program’s success, providing students with concrete goals and aspirations, such as maintaining a 2.0 minimum GPA.

In the program Martz and Blanchard were affiliated with, in 2016-2017 and 2017-2018, more than half of students were either still enrolled or graduated with a high school diploma. Many students earned college credit, and some earned an associate degree, certificate, or were on track to earn an associate degree.

For a cohort of Open Doors participants during 2015-16, students who spent more time in Open Doors were less likely to drop out than students who spent less time in the reengagement program. In addition, students who dropped out of high school and participated in Open Doors graduated and enrolled in postsecondary institutions at twice the rate of students who dropped out and did not participate in the program. The participants in the cohort were disproportionately more likely to be Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino. They were also more likely to be from a lower-income background.

Justin credits Open Doors and his mentors with enabling him to graduate in 2020 with a high school diploma and associate degree in business. His success in Open Doors also led him to apply and be accepted into UW. After Chemistry and Biology classes piqued his interest in science, he plans to major in microbiology and social work.

“The incredibly meaningful role models I met…genuinely cared for me as a person and were there not only to guide me academically, but to be a support when I was struggling in any way,” Justin said. “If not for the amazing mentors and role models in Open Doors, I would certainly not be where I am right now.”

With an interest in a career in psychopharmacology, Justin hopes to eventually to pursue a master’s in social work and evaluate whether to pursue a PhD in pharmacology or neuroscience.

“My goals are somewhere along the lines of helping to reduce to the suffering of all living beings and contributing to the world in any way I can,” Justin said.

Teeters, who graduated in spring of 2021, is excited to look for careers with his degree in network technology and computer security.

“Honestly, the biggest skill I learned was confidence, not completely giving up on yourself,” Teeters said. “Advisors not only encouraged me but gave me advice and were so willing to meet with me and talk about issues or figure out solutions. I left high school feeling like the biggest failure. Less than a month after starting Open Doors, my advisors not only made me feel totally opposite of that but also gave me the ability to enjoy school and find passion in things.”

He hopes that more students learn about Open Doors.

“I think a lot of young dropouts or people struggling with traditional schooling could benefit from it,” Teeters said. “Open Doors is something very special as it’s a chance at college for people like me. With so many barriers to school for people getting an opportunity to have a full scholarship, to get not only a degree but a diploma is pretty big.”

Advice to schools interested in starting an Open Doors program

A dual credit Open Doors program cannot exist without partnership between a local district and a community or technical college, Blanchard and Martz said. School districts and colleges must partner to agree on funding, admissions standards, programs, and more. School or district staff typically refer students to Open Doors programs at a partner college.

Blanchard and Martz share key lessons learned and advice for school staff who are thinking about starting an Open Doors program.

- Flexibility is key. Try different models based on student needs. Make sure the program does not perpetuate failure without providing supports. Know that program models may not be successful the first or second time.

- Build relationships with surrounding high schools, agencies such as Youth Eastside Services for counseling, and partner programs such as Friends of Youth and Graduation Alliance.

- Take an active interest in students. Encourage relationship building between teachers and students, advisors and students, and among students in the program.

- Set clear, realistically attainable, and transparent standards for behavior and academics (such as GPA requirements). When past students have not met the standards, counselors have referred them to partner programs, and sometimes students return when they have a more secure support network and home situation.

- Be prepared to talk to students undergoing mental health crises, using a trauma-informed approach.

- Have emergency food on hand for students.

- Provide initial information sessions for prospective students and families who would like a clear understanding of the pathway to high school graduation. Offer the sessions in multiple languages and through multiple avenues, such as virtually.

- Communicate with students in a variety of ways, such as social media, text (through apps like Remind), and email.

- Hold students accountable. Sometimes advisors may need to follow up with a parent or guardian.

- Treat students like adults and maintain professional boundaries.

- Stay positive about students who do not graduate from the program. They may have earned college credit or made progress toward a high school diploma. Perhaps students improved their attendance, communication, or their classroom presence. Refer students to programs that will work better for them.